Introduction: Debunking Myths about Fairy Tales

I have been studying and publishing on European fairy tales for nearly 30 years. I first took a course with Jack Zipes in the early 1990s, and my first published article on fairy tales appeared in 1998; I have published on fairy tales and their adaptations from the sixteenth to the twenty-first century ever since. I have also been teaching fairy tales for just about as long, and as someone who is grounded in the early modern period, I saw a lot of students and even scholars of contemporary fairy tales who had a lot of misconceptions about the history of the genre.

These misconceptions have a lot to do with the ways in which people read our contemporary canon of classic fairy tales into the past, which assumes that tales that have been popular since Disney's Snow White, Cinderella, and Sleeping Beauty--which led to the popularization of certain tales by the Brothers Grimm and by Charles Perrault--were always held in the same esteem over the centuries.

Feminist revisionist writers like Anne Sexton, Angela Carter, Emma Donoghue, Margaret Atwood, among many others, rightfully reacted to this male-dominated tradition that began in the twentieth century. However, they are reacting to a post-Disney fairy-tale field, which has given rise to the common perception that the field of fairy tales has always been dominated by Perrault-Grimms-Andersen, by Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and Little Mermaid tales. This has resulted in a misconstrued conception of the fairy-tale universes of different countries and different periods in which women often played prominent roles and many a fairy-tale heroine proved capable of saving herself and others, and of preserving and ruling over kingdoms.

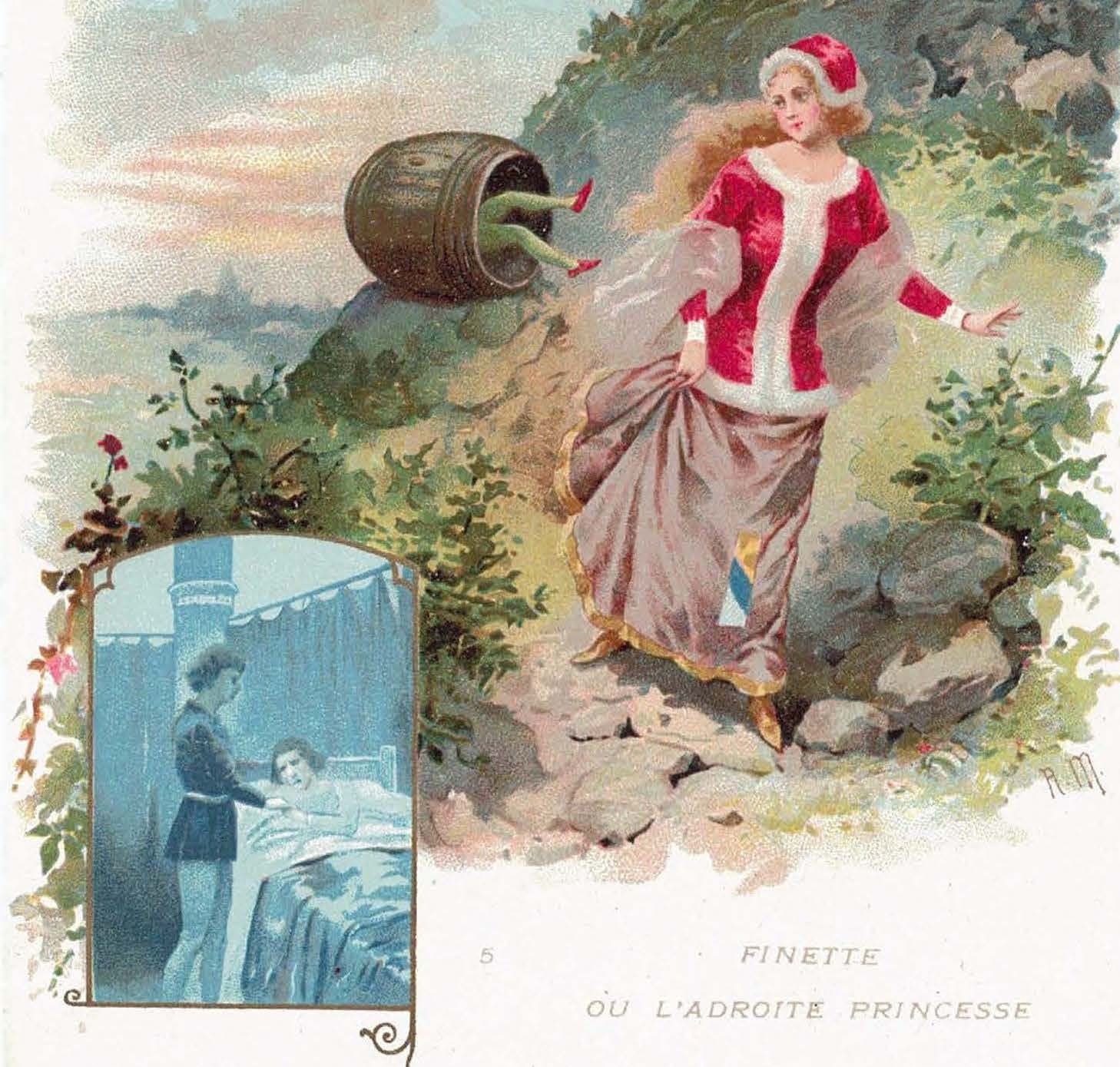

In the seventeenth century Giambattista Basile's "The Cat Cinderella" kills her first stepmother yet is rewarded with the hand of a prince; Marie-Jeanne L'Héritier's Finette fatally wounds a man who seeks to assault her (the image accompanying this post is a detail of her story depicted in an 1890s department store ad); Marie-Catherine d'Aulnoy's crossdressed knight Belle-Belle/Fortuné saves kingdoms. "Finette" and "Belle-Belle" were popular tales in France, Germany, and England through the nineteenth century: they didn't simply disappear at the end of the seventeenth century.

As these few examples make clear, the post-Disney perception of the fairy-tale field does not accurately represent the past and in fact effaces the more dynamic gender relations and the roles women writers played in the history of the European fairy tale. Marie-Catherine d'Aulnoy's "The White Cat," first published in 1698, was one of the most beloved fairy tales in nineteenth-century France and England, featuring a strong and sovereign heroine; it was at least as, if not more, popular than Perrault's "Cinderella" in Victorian England.

Through blog posts by specialists, I hope to bring to light the voices that have shaped the history of the European fairy tale that have been effaced by the hegemony Disney has exercised over "our" conceptions of the genre. I also hope to bring in scholars to address other accepted but unexamined preconceptions about other aspects of the fairy tale. We will look at changing fairy-tale canons in different historical periods and geographical locations; question some of the accepted wisdom that written tales are always based on oral tales; ponder the ways in which fairy tales fit--or not--into nationalist discourses. I also invite readers to comment and also correct information on the information presented in posts.

Posts should appeal to both fairy-tale enthusiasts and scholars. For me, the idea of debunking myths about fairy tales is about re-examining idées reçues or commonplace beliefs about the genre that don't necessarily hold up to close scrutiny. Often it is about challenging any kind of overgeneralization about fairy tales. What might be true in one period often is not in another; also, tales have often been repurposed for different ideological needs, so we need to keep in mind that the same tale can mean different things to different people in different times and places. The idea of timeless tales that have no history is the most important myth to be debunked through this blog.